Bacteria from untreated sewage frequently causes beach closures across Long Island Sound

June 26, 2019 | By: Christianne Marguerite

© The Nature Conservancy in Connecticut (Rachael Lowenthal)

High bacteria levels from untreated wastewater entering onto our beaches during heavy rain events cause closures, common across Long Island Sound. This halt on recreational activity in impacted areas is not only a nuisance when you had beach day plans but can also sometimes be a big hit to the area’s economy. The presence of bacteria also poses serious health risks to people and wildlife. We can work to decrease the frequency of beach closures by upgrading and modernizing old and deteriorating wastewater systems in coastal communities, supporting clean, healthy beaches for all to enjoy.

With public school children out of classes and the summer weather in full swing, families, couples, and individuals from far and wide are flocking to the myriad of beaches across Long Island Sound (LIS). Whether you are hoping to go swimming, fishing, boating, or just hanging out in the sun, both the New York and Connecticut coastlines have plenty to offer, and the states are dependent on these recreational and commercial uses of the Sound. In fact, LIS generates about $9.4 billion annually for the regional economy. It is crucial that we invest in the protection of the water quality of LIS to ensure its use for generations to come. We can start by fixing the issue of raw sewage contaminating our beaches, which puts the health of our wildlife and our communities at risk.

The region has seen rapid growth and development since post-colonial settlement in the 1600s. There are now around 23.3 million people living within 50 miles of LIS and millions more visit the area each year. In 2018, there was a record of 65 million tourists in New York City alone. While this is great for the economy, these vast numbers can be difficult for our outdated infrastructure to handle. Just like our roads, water infrastructure – including storm drains, sanitary sewers and old septic systems – were not designed with so many people in mind. The growing population, along with a changing climate, puts continued stress on a water system that is already over capacity.

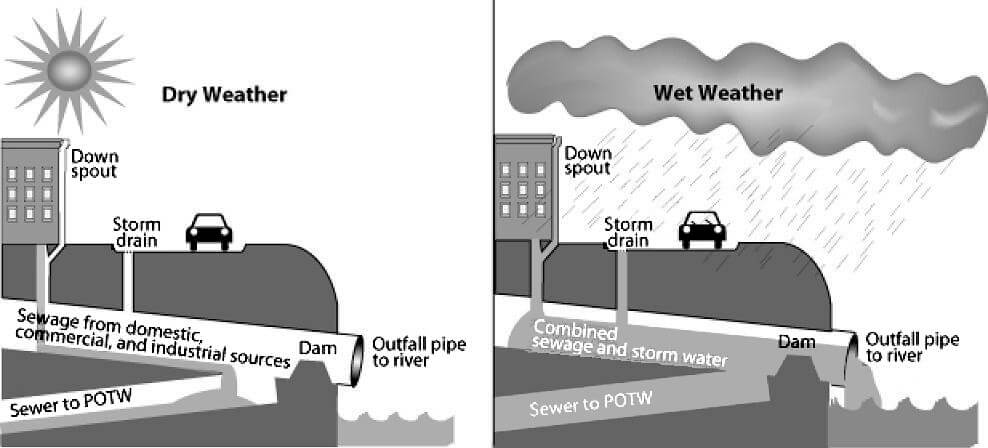

Systems in which rainwater runoff, domestic sewage and industrial wastewater are collected in the same pipes are known as combined sewer systems. During periods of heavy rain, these systems that are already very full cannot handle the added water so they overflow, known as a combined sewer overflow (CSO). This can be very dangerous to public health because the untreated human and industrial waste that pours out of the system discharges into nearby water bodies like LIS.

© U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2004 EPA CSO SSO Report to Congress, Chapter 2 Background

Many of the communities around the Sound, including the major urban areas, smaller urban areas and dense suburban areas, were built on combined sewer systems that too often overflow. This major pollution issue is one of ecological, public health, and economic concern, and degrades the overall quality of life along the Sound. Even in areas that don’t have CSOs, bacteria and nitrogen pollution from septic systems and cesspools can enter recreational waters through groundwater, threatening human health and leading to algal blooms that deplete oxygen and suffocate marine life. The fecal bacteria present in sewage and stormwater runoff can cause people gastrointestinal illness and infections of the eyes, ears, nose, and throat.

Communities close local beaches to prevent residents from entering contaminated waters and getting sick. However, beach closures are hard on local economies – causing towns to lose money from admission fees, concession stands, restaurants and tourism businesses, so once the bacteria levels drop back down to being acceptable, they are reopened. Because closed beaches are so common around the Sound, the Long Island Sound Study set a management goal to reduce the number of beach closure days by 30 per year.

The decision to close the beach after heavy rain is up to the individual town and some may instead choose to issue an advisory warning that residents can swim at their own risk. Even at closed beaches, some fecal bacteria may still be present in the water after reopening, continuing to pose health risks to people. Climate change only exacerbates this problem by altering the frequency and severity of rainfall and increasing water temperatures. This leads to more fecal bacteria and nitrogen pollution from runoff, CSOs and outdated septic systems and cesspools entering warmer recreational waters where bacteria growth and algal blooms worsen. We can stop pollution from sewage entering our coastal waters by updating and modernizing water infrastructure to reduce polluted runoff and eliminate CSOs, and using septic systems that treat more nitrogen and pollutants before discharging into the groundwater.

The longer we wait to fix our water infrastructure, the harder and costlier it will be. Communities can push for government support and investments in infrastructure and new technologies that boost clean water jobs and build healthy economies. To help make this happen, residents can speak in person or write letters to their local, state and federal officials. Ask leaders to support clean water funding and adopt policies that eliminate CSOs, adopt policies that enable stormwater authorities and permit the use of proven alternative treatment septic systems. Educate fellow residents about the risk of bacteria from untreated sewage on the beach and let them know that by investing in water infrastructure, we can protect the health of the Sound, make our water cleaner and make our beaches safer now – and for future generations. Remember, anyone can make a difference. What will you do?